Sol.a.stal.gia. (noun) Definition:

“Solastalgia occurs when someone feels a sense of anxiety, grief, or loss due to the degradation or alteration of their home environment. It is the inability to find solace in one’s surroundings.”

Loss & grief for things like beloved spaces.

the idea of sweeping the slate clean, like there’s nothing here of worth.

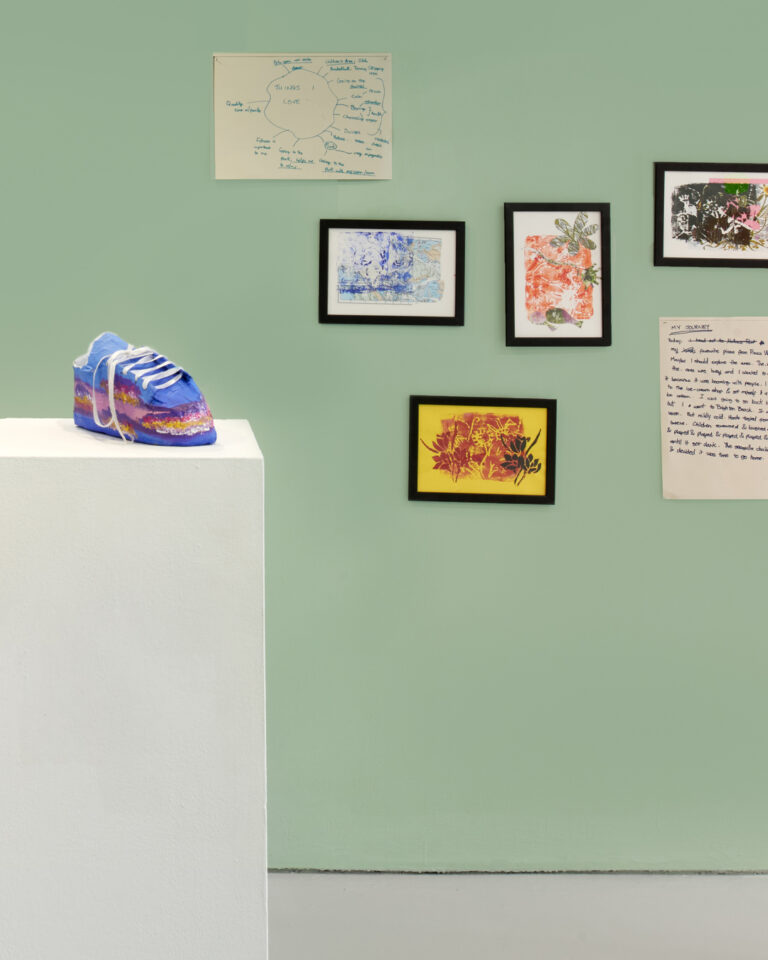

As of our Desire Paths year, Turf has now been existing in temporary spaces for 10 years.

As local young artists we found a lack of opportunities and space to make and show work – so we decided to create our own. For our first 2 years (2013-15), we had no fixed home, putting on projects in public spaces.

We moved into our first ‘proper’ space on Keeley Road (now called ‘Little Turf) via crowdfunding and a GLA Meanwhile Use programme. Little Turf was a nook where the sun beamed through between retail monoliths. Old school sandwich shop lunches burst out with fillings, keeping company with the absolute gents at Budwal’s, kids spilling out of daycares, 101 Records on the corner.

After two years we were told we’d lose the space due to developers’ plans. Turf moved to one of the many large long-term empty spaces in the then ‘soon to be demolished’ Whitgift Shopping Centre; such units being plentiful when commercial operators are reluctant to invest in spaces with an uncertain future.

Following our move, planning permissions lapsed; we never got served notice on Little Turf and it currently hosts local co-conspirators RESOLVE Collective. However, like other leaseholders in the Whitgift, and like many others nationally, we still face losing our current spaces at an indeterminate time on the horizon.

When shaping up the Desire Paths project, we thought a lot as locals and as a team at Turf about our relationships to the built environment & decision making processes. Our history of being dependent on and restricted by whoever held power over our spaces; the frustration that spaces were sitting empty whilst community need soared, the idea of those of us with spaces all just keeping the seat warm for those to whom it really belonged.

These processes are driven by faceless forms which see only ‘investment potential’ without seeing our childhood selves throwing pennies into fountains now full of grit, the routine of greeting familiar faces on the route to a now shuttered Sainsbury’s, the way Whitgift’s glass roof feels like a greenhouse when the sun is shining or how the sound bathes you when the rain pours. How at night, when everyone’s gone home and the escalators wind down, the silence covers you like a blanket.

Desire Paths explored the idea that stability and trust in a familiar built environment can form part of the roots of peoples’ sense of belonging. Drawing from local space-specific projects like Croydon Saffron Central, a crocus farm on the site of the former council offices; Lost Format Society’s car park rooftop cinema; and community hub Socco Cheta, Desire Paths aimed to use art as a vehicle to connect spaces and decisions made about them with their human impacts – on wellbeing, sense of worth, what and who is permitted to exist and take up space. Mapping the invisible spaces of power, power as it relates to or becomes represented in physical space.

So many in our borough still talk fondly of Turtle’s, a local family run hardware store pushed out along with other long term tenants of St George’s Walk in favour of the failed visions of multiple developers. Fifteen years on, the site still sits demolished and devoid of any use. Matthews Yard, a community venue without which many other local organisations, activities and relationships may not exist, suffered the same fate at their space off Surrey Street, whilst ‘culture at the heart of regeneration’ was still the buzz phrase for overseas investors. Scream Studios, chaotic home to many a local teenage band, was demolished in 2019 with planning conditions for ‘music rehearsal and event space at ground floor level’ which has yet to materialise.

Following Croydon Council’s financial collapse, we have also seen local publicly-owned spaces sold off; excluding communities who cannot compete with developers to offer market rates (no matter what their ‘social value’). When spaces do become empty, risk aversion makes owners and the local authority unlikely to take a chance on small organisations over a ‘safe’ bet; lucrative selling, letting or demolishing to or by those who have the resources to acquire more resources (though this doesn’t always pay off; see Carillion, R&F).

Spatial planning systems have by their overwhelming complexity become disconnected from their relevance to everyday life and from the human implications of decision making. That which already exists, or could be, is left struggling to establish, stabilise and grow, drowned out by the grand visions of a curated few who have the resources to comprehend and play these systems, to shout louder for longer. In the process of Desire Paths, several of our case study spaces were sold or granted permission for redevelopment. Some we were told were unsafe to use were permitted use by commercial operators. Two were set on fire.

The Cartoon, St Edmunds, Warehouse Theatre, Cherry Orchard Garden Centre.

Like a mature tree replaced with a sapling, once lost to the community we can’t engineer a glossy replacement for these spaces, and even if we try, we cannot expect them to function in the same way or mean the same thing.

Segas House, Surrey Street Pumping Station, The Leslie Arms, Heathfield House.

Once in the hands of market forces, there is little we can do to prevent spaces from being left empty, waiting, stagnating.

There is certainly a type of grief in having no power over what happens to an environment around you that you cherish; an imbalance in control that is rarely acknowledged by those powerful and privileged enough to be making decisions.

Regeneration by its nature is preceded and fuelled by processes which encourage insufficient levels of ongoing care interspersed with flurries of change, making some very rich whilst leaving locals with the jarring disconnect of familiar environments rapidly altered. It tells communities that spaces they care about, that keep them rooted in place, need razing to the ground and rebuilding to meet the standards and big visions of those who will never use, work or live in them. Through this accumulative disconnect, we have watched a sense of belonging, collective emotional memory and community cohesion be lost.

With rapid and prolific change well regarded to have negative impacts on mental health, why promote it in our built environment? How could we not mourn the loss and unrealised potential of familiar spaces which may have nurtured and sheltered so much that we love?

What we really want to see is spaces prioritised for our community. However, perhaps there is still autonomy and power in owning our collective grief for beloved spaces lost and empty, even if that doesn’t immediately translate to physical changes. These frustrations fuelled peoples’ interest in Desire Paths and brought people together. Alongside the community, the artists explored how the spaces around us can physically and tangibly mould a thousand intangible experiences; the routes we take to work, how safe we grow up feeling, from where we’re excluded, how easy it is to care for a vulnerable loved one, whether we ever learnt how to swim or ride a bike.

Desire Paths toyed with a different big vision; how spatial decision-making processes could work if more democratic and accessible to all. Spaces full of pain like Reeves Corner, where House of Reeves burnt down in the 2011 riots, were awoken for the first time in years, connections were made and memories exchanged between people who would never usually have met.

In the midst of the undercurrent of grief we still find ways to carve our own spaces like Turf to feel sheltered from it all, even if it’s just an illusion. From here we spring through cracks in the concrete towards the sun.

With huge thanks to Rosie Crane Eckmire, Natalie Mitchell & Caleb Pinnell for support and feedback in writing this piece.

Share: