Once upon a rainy day in Croydon, there was a Beast.

The Beast was made of an exuberant arrangement of lines, shapes, limbs, and faces in all possible colours.

It rolled out of the first floor above Turf Projects, scrambling over the balcony, hitting the ground with a boom. This was both pleasing and impressive. Then it tidied itself back up, ascended the escalator in a civilised manner, and sprawled across a different bit of the balcony so that everybody below could admire its splendor.

***

There is a game you may not have heard of but almost certainly played. It’s called Exquisite Corpse or Picture Consequences, and it is about the pleasant jumbling-up of information.

I will tell you how to play it:

Firstly, at least one other person is required. (It may be possible to play it with yourself if you are particularly forgetful, or exceptionally creative.)

You will need a piece of paper and some sort of drawing material. Draw or write something onto a small section of the paper, fold the paper to hide most of it, and pass it to your partner, who will make their own contribution. Continue doing this, passing it round all your players or back-and-forth between the two of you, until the paper is completely folded up with your secrets.

Unroll the paper and consider what you’ve created together. It is probably funny, which is nice, because most secrets aren’t.

You could keep playing just like this. I am assuming that you’re using ordinary drawings things and playing in the privacy of your own home. But this sort of game mutates and scales up gorgeously while staying true to a simple, low-stakes kind of fun. It’s nice to have a game where there’s basically nothing to lose, even if you peek—and even then you do not totally remove the main element of surprise: your fellow players’ reactions, and what you might decide to do next.

***

Once upon a rainy day in Croydon, we played Exquisite Corpse.

I started the game by inviting other people to come. This was not limited to ~Artists~. Anyone who wanted to participate could do so.

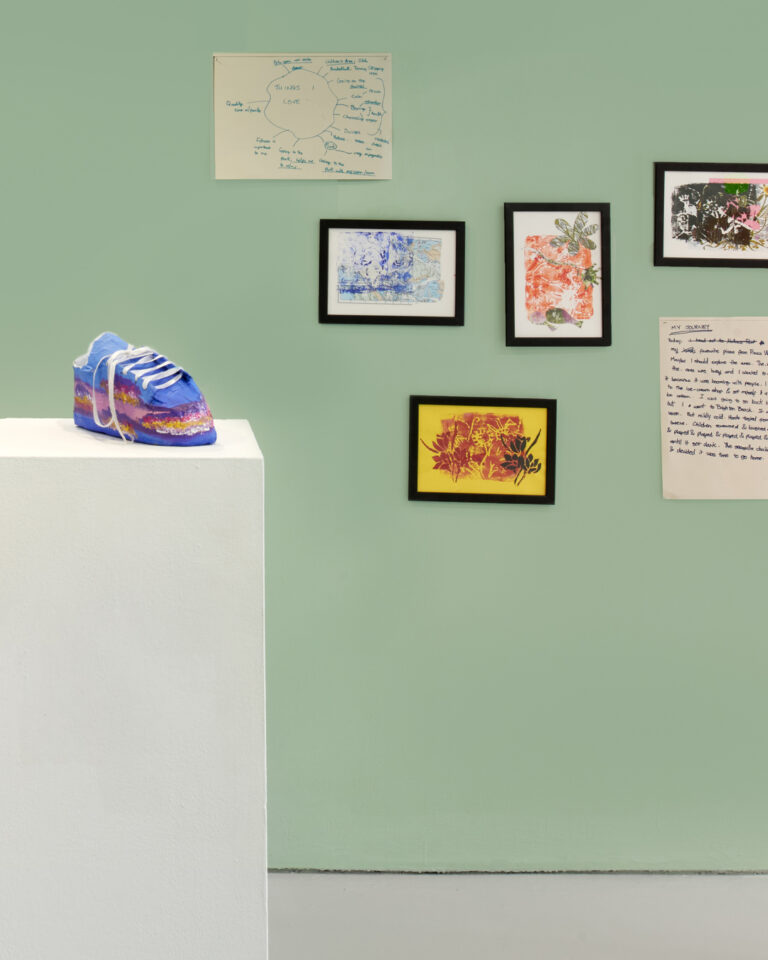

We used a big roll of paper, the kind a medieval herald might crack open and make pronouncements from in a horn voice. In the windowed space in Turf Projects, a group of us gathered inside and watched each other draw while passers-by outside peered through on their Saturday jaunt through the Whitgift centre. At our disposal was a whole arsenal of drawing things: lovely thick chalk pens that leave painterly marks, a rainbow of felt tips, and coloured paper tapes. Within the structure of 5 minutes per drawing over 2 hours, we created a huge drawing that took over the space.

What were we drawing? Well, nominally a Beast of Croydon. I was very excited. I envisioned engaging with the ugliness of Croydon and refusing to permit its prettification; unleashing our beastly selves, indulging in everything the ruling class tells us needs to be controlled and capitalised-upon. I wanted to say NO to being encased in firstly a shiny suit and then a shiny glass office and then going home to a shiny glass flat to stare at a different shiny glass screen. I wanted to say YES to the body that is unruly, a body that refuses to be subordinated and disciplined. I wanted opulent disgust, many-limbed excess, teeth and legs, eyes and claws, a fine snapping jaw to bite the hand that feeds and wrench it off at the shoulder!

But in the end I just said to people: draw what you like.

I only kept the timing tight. It had become quickly apparent to me that the very act of drawing was important in this activity: the act of choosing materials, putting them to paper, translating ideas through your arm, having a different idea, choosing another material, switching colours, and so on. Five minutes is both longer and shorter than you think (“300 seconds!” said one of the younger artists). No time to agonise, just enough to get something out.

The fact that this happened in a room with other people watching meant that participants were required to have a certain level of boldness for 5 minutes. This didn’t necessarily mean everyone was a show-off; rather, we created another meaning of the word “draw,” to bring closer, move towards, bring together. Once some people started drawing, other people wanted to draw. It is not a big deal, everyone does it, and it’s fun.

I said, “Whatever you draw will become a monster.” A monster has as many body parts as is necessary to get from beginning to end. They can be recognisable and abundant: lots of eyes, legs, grinning faces, silhouettes of human extremities. They can extend beyond what is immediately familiar, like a wiggly line describing a boundary of lumpy skin, or maybe a spiky shape becomes a rib cage; a colourful loops seem like shining scales, while swirls and scribbles become hair, tentacles, or suggest that we are dealing with an amorphous shapeshifter. Our monster existed at different levels: as cohesive beastliness, as records of personal drawing styles, and as a huge collection of information that was indexed at one particular time and place—the monster ends by pointing us towards Turf Projects.

***

Once we were done, we rolled up the drawing completely. We had no idea how big it was, we had to regularly pull out more paper, gobbling up metres of the roll with our colourful marks and gestures. I thought of hanging it from the ceiling, but another artist had a much better idea: do a banner drop.

As we discussed how to reveal our drawing, how to comprehend something unknown and in all probability rather large, I became conscious of how our artmaking, how our bit of fun for the day, was brushing up against The Rules. We were, after all, in Whitgift shopping centre. Spaces like this have all sorts of unspoken rules, sometimes permissive, sometimes punitive… if you get caught.

André nobly decided to take responsibility for doing the drop. He went upstairs with the paper while we gathered outside on the ground floor. There he was, high above! He held our monster aloft, counting down before letting it drop, and the paper cascaded downwards in a rush of colour, hitting the ground with a boom before carrying on with its journey. We welcomed it with a round of applause.

We decided to do a second banner drop, this time unfurling it lengthwise across the first floor balcony, a group of us co-ordinating rolling, unrolling, and re-rolling between us. It took many pairs of hands to handle this length of heavy paper. Through our movement we extended our drawing into the real world.

***

This workshop is drawn from my experience of being taught by Harriet Hedden, my Foundation tutor at the Mary Ward Centre. Her session featured a fun, quick sculptural response to an exquisite corpse drawing. I was keen to include this in my Propagate This! workshop.

But on the day, there wasn’t much more to be done. My intention was different here – I thought we needed to realise things from our drawings, but we had already made our mark on the space.

Back inside Turf, we rolled the paper across the bottom of the wall like a mural, and it felt different to understand the Beast as the size of a room as opposed to something taller than a shop front and able to cover a side of a balcony in a shopping centre. We further transformed the Beast by asking questions about it: What does it eat? How was it born? Who is she?

The act of applying language to it made me consider the drawing differently.

It was a Beast made with simple rules, but it had already had such a life in one afternoon.

***

While thinking of our jumbled-up monster and how we made it, the term “assemblage” comes to mind. It’s one of those horrifying words often used in poncey art contexts to show off how smart you are, but I still like it as it’s clearly related to an everyday word, “assemble,” putting together, DIY.

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, author of The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (2015), defines assemblage as an “open-ended entanglement of ways of being”:

Assemblages don’t just gather lifeways; they make them. Thinking through assemblages urges us to ask: How do gatherings sometimes become “happenings,” that is, greater than the sum of its parts? If history without progress is indeterminate and multidirectional, might assemblages show us its possibilities?

Tsing explores the collaborations of fungi, land, and humans, discussing ideas around trespass, freedom, accumulation, and surviving collaboratively. I saw similar themes as we made the drawing together and took it outside. Maybe it isn’t that deep, but I’m still thinking about it days later.

***

Until the early C19th, much of Croydon used to be common land. This might provoke visions of community ownership, happy shepherds and flocks gambolling across the hollows and dells of Arcadia, but as Dr Katrina Navickas points out, it usually meant that local communities had certain common rights to land that was still privately held. So it wasn’t that Enclosure of common land resulted in the poor suddenly being dispossessed: that land was always owned by the few.

The Paget Deeds tell us that in 1595 one Clemente Banks sold an inn and some land in Croydon to John Whitgift, the archbishop of Canterbury. That inn became a school, and then, hundreds of years later, Whitgift shopping centre. The rest of Croydon was steadily bought up over several Parliamentary Inclosure Acts between the late 18th century – early 19th century, which was carried out all over England with the goal of making the land more “valuable,” that is, profitable.

Do you see where I’m going with this? Now, I do not say all this just to draw an easy historical parallel, slyly lending rhetorical weight to an implied critique of the present; indeed, as Navickas has emphasised, eliding issues of land usage and land ownership, blurring the line between the right to roam with common land, has resulted in many ahistorical misconceptions—if you were to make a proper study of either, you’d be researching different legislation, history, movements etc. Language is important. However, for the purposes of this post, I bring up common land to show that our relationship with where we live has always been a shifting process, mediated through not only laws but customs, arrangements, certain understandings, and myths. Over time, notions of ownership, use, movement, settlement, and obligation have changed. What does all this history mean for us now?

I don’t propose that we seize Whitgift and turn it over to productive agricultural purposes, even though it might make a splendid greenhouse (in the utopia I envision I would like this very much). But maybe, in an ironic turn of phrase, we could begin by de-naturalising the space of a shopping centre.

A lawyer explained to me, using the phrase “vampire rules,” how implied license works.

So: you are likely to be trespassing on any bit of land unless you have permission of the owner or person legally in charge of the land. For types of land that are normally accessible to the general public e.g. shopping centres, roads, private squares / parks etc, there is something called implied license which means you don’t need explicit permission from the landowner every time you want to enter, because there’s sufficient external circumstances that make it clear the general public are allowed to come in.

However, that license can be for a specific purpose, rather than just permission to come in and do whatever you want. “Implied” license is normally license to enter for purposes tied to the owner’s particular wish. In the case of shops, you can come in, browse, and buy things.

The law of trespass is more restrictive than vampire rules. If you invite a vampire into your shopping centre, they can come in and go here and there sucking people’s blood with impunity: that’s vampire rules for you. Now, you, an ordinary person, can freely enter a shopping centre, but your movement is bound by rules the entire time. There doesn’t actually need to be any clear signage to show where you’re permitted to go and what you’re allowed to do. The landowner or his agents (e.g. security staff) can at any point revoke permission verbally or by chivvying you away, and if you don’t leave within reasonable time, you are now “trespassing” or “loitering” or whatever activity that isn’t the polite consumption of goods. Suddenly, it becomes very clear that a shopping centre is built not only from glass and metal but from rules that sit on top of a large quantity of land, land that is owned by someone, and that ownership means having the right to constrain the behaviour of all who enter.

You might think this is not a big deal and I sound like a crank: it’s just a shopping centre! If you’re not doing anything wrong you don’t have to worry about anything. True, if every rule were constantly invoked and enforced in every situation, daily life would be impossible. In this situation, some artists certainly got away with having a little fun.

But what I said is true outside of Whitgift. In England and Wales, all land is owned by somebody, so you are constantly moving through a net of rules. You are actually not free to go anywhere and do what you like, and some of us are forced to realise this much sooner than others. We live our lives until the rules make themselves known to us, and depending on our position(s) in the social order, we experience the intrusion of rules upon our life with varying degrees of violence, restriction, inconvenience, sometimes all of that, sometimes none.

So it isn’t that you individually are good and law-abiding, it’s that daily life within the status quo relies on you slipping through the net and going unpunished. We exist at the sufferance of a state which, as the authors of Empire’s Endgame have observed, increasingly offers authoritative punishment in place of social welfare. And we have been so materially and spiritually ground down that many of us celebrate this, while those of us horrified by the status quo cannot imagine an alternative.

What is the role of art in such a world? After the art happened I researched and wrote this piece. The art was the thing that I sought to understand, but it wasn’t the art itself that did the uncovering and analysing. The art was experienced, hand to pen to paper.

***

I mean, yeah, alright, a drawing game didn’t immediately transform power relations.

It would be much too easy for me to conclude that art can change lives! art can change the world! but we have to be very clear and honest about what kind of art, by whom, and for what purpose. Developers know that art can change property prices. The state works its soft power in and through art and culture; neoliberalism values innovation that comes with creative thought. We’re encouraged to think a degree of permitted eccentricity is the same as freedom, rather than a pressure valve. If we were actually doing something that threatened the world order, we would very much know it—the state has the ability and motivation to neutralise legitimate threats to its control, whether that’s through acute / attritional violence or assimilation.

I am still not willing to give up on the role of art in the theory and practise of liberation.

The funny thing about art is its usage for obscuring things, even the conditions of its own making. The art world is where the laissez-faire and neoliberal collide, outrageous commodities, marketised art schools, and competitive funding structures jostling against each other. It all relies on scarcity as the starting point—that you have to be the best at delivering the art experience, at creating value, at contributing to the accumulation of social and / or financial capital, or you don’t deserve any resources for it. And we’re supposed to put up with all this for the sake of art, the thing that makes it all better, the modrock smoothed onto the chasm of capitalist deprivation.

Despite this, what I keep coming back to is B saying that when art processes are made visible at Turf Projects, it ignites people’s curiosities. Art attracts people and still has the potential to interest them in all the materials and ways of making stuff in the world. Above all, art is fun to do and makes us feel important. This simple, somewhat childish way of thinking about art feels more honest than trying to make it perform grand philosophical or liberatory gestures. I think it’s crucial to also be honest about how art won’t immediately free us in a material sense, but art can still attract people to freedom in many ways, not least because it is one more possibility that brings groups of people together, the starting point of any meaningful change.

Propagate This! happened because Turf arranged it: they worked to get funding, bring everyone together, and support us throughout the project. They gave us transparency from the very beginning, so we not only saw how artworks can be made, but how we can arrange the conditions for making creativity possible. Art is not the magic that happens at the end, a return on the investment, art is just one possibility in the roots that push out from this point.

The question isn’t only “What are the problems that need solving” or “How do we create change?” but also “What are the things we require to be able to organise in the first place?”

There are urgent practical needs to be met: money, childcare, healthcare etc. The soul, the willingness, the motivation follows that—I don’t mind being a bit determinist about this. Why hope that art (and really “art” can be replaced by any human activity) will vaguely empower individuals to create change when we could actually organise? Why wait for someone else smarter than you to say, “Wow, your idea is great, let’s do something”? Change starts from the bottom-up. You don’t need to be the most qualified person in the room to start something, you just need to be honest enough to understand that you can’t do this alone. If we’re already having conversations, then turn these conversations into a meeting at a time and a place. That meeting will probably be small. That’s always how it starts. What matters is that we know we can agree to interest ourselves in something and see it through. We have the power to lay down roots.

That said, disarranging is also important. What made the Beast of Croydon so fun was that the suggestions came spontaneously: I did not plan for the art to go outside of the Turf project space. I gave up some of my control so that people could make stuff happen. I am not sure that everyone who was there would agree that they were ~Artists~ doing ~Art~; I could write something really annoying about doing socially-engaged participatory performance art that was super successful and intentionally resolved, but that would be incredibly dishonest and diminish what we made. The open-endedness was important. That unexpected non-linearity does not jibe well with a system that demands you perform your deservedness within a project timeline, so I commit to continuing not to know and feeling my way through.

Maybe the end point is not more art or more artists, at least not in the way that we currently understand this cultural enterprise and occupation. Maybe there is no end-point, maybe art is the point of departure; or rather, maybe art is not an escape from real life but a way back into it.

None of what I am saying or doing is new and original. I am exhausted with innovation. I return to the ground.

***

After we made the Beast, we all went home.

The rain slanted under my umbrella, and it did a wonderful job of soaking me to the skin through thick denim, obscuring Croydon’s new skyscrapers under soft milky haze, and becoming a perfect shining black inkily puddled in the streets of Camden.

I thought about how rain is both nourishing and destructive. How the matter is what matters: the infrastructure, the substrate, how the thing that holds us all needs repair. I thought that if Turf is the mother spider plant and we artists are the baby spider plants, then Croydon is the soil. I thought about how things appear after the rain, shallow clinging moss and lichen revived from dormancy, hyphae secretly fruiting mushrooms. They are little things on the ground, clustered, networked, spreading broad and deep, sometimes surprising you with where they end up and re-appear.

There are many ever-afters.

Share: